'Reflections' Wellington Dam, Western Australia

Collie, Western Australia,

2021

Wellington Dam Mural, Wellington National Park, Western Australia, March 2021 Photograph: Guido van Helten

Reflections features archival photographs sourced from local communities that explore collective memories of the Wellington Dam and Collie River Valley, located on the land of the Wilman Noongar people.

Photographs by Guido van Helten, Frances Andrijich, and Roxanne Taylor

Project Details

Project

'Reflections' Wellington Dam, Western AustraliaLocation

Collie, Western AustraliaCommissioner

Collie Mural Trail, initiative of the Department of Premier and Cabinet, Western AustraliaThe Wellington Dam District Map, Western Australia, September 2020 Guido van Helten

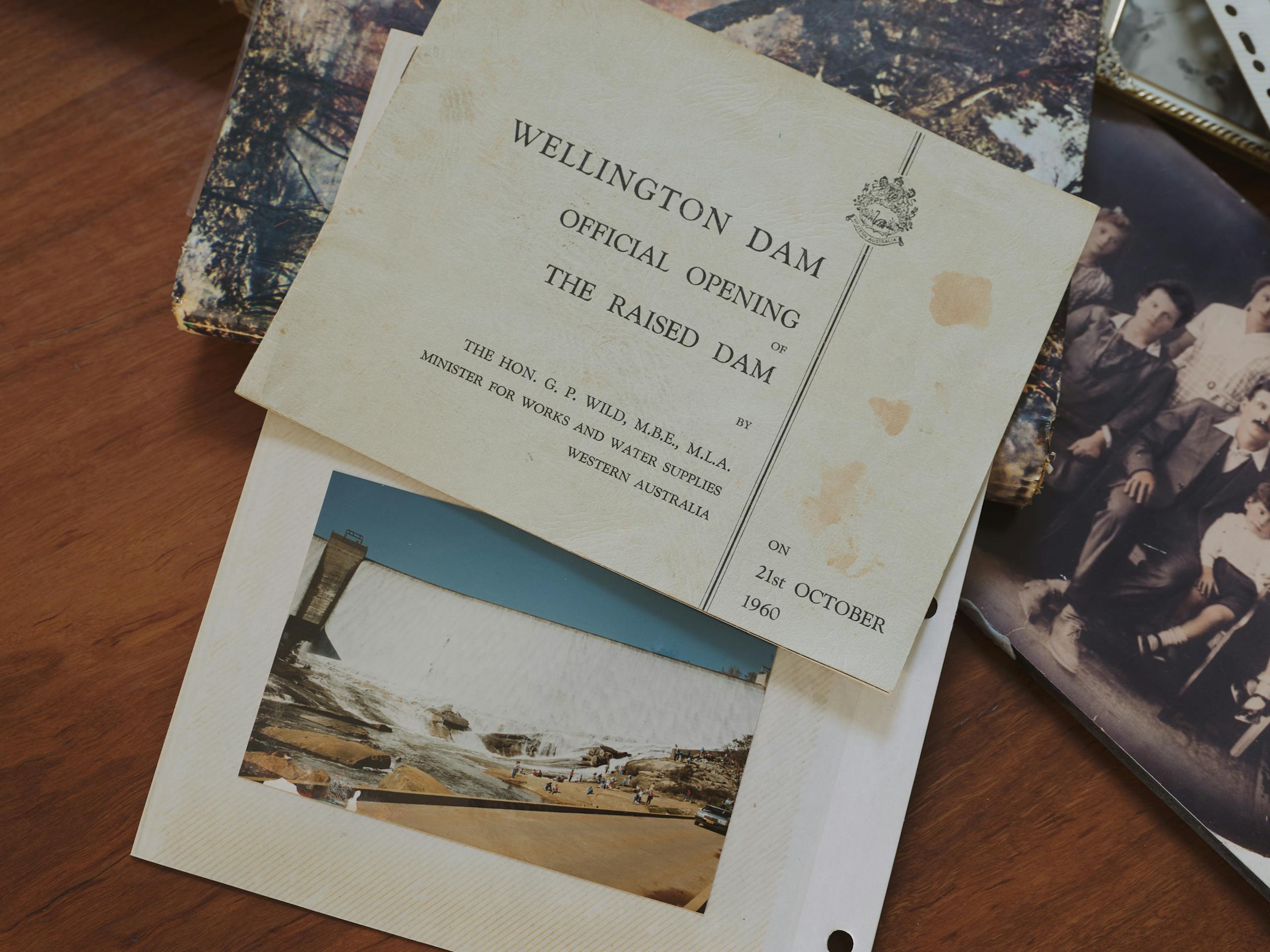

Rusconi family photo albums, Western Australia, September 2020 Guido van Helten

David W. Blight, Common-place (2002), Historians and “memory”

If history is shared and secular, memory is often treated as a sacred set of absolute meanings and stories, possessed as the heritage or identity of a community. . . . Memory is passed down through generations; history is revised. Memory often coalesces in objects, sites, and monuments; history seeks to understand contexts in all their complexity.1

South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council (n.d.), Noongar Protocols. Noongar country covers the entire south-western portion of Western Australia. The Noongar people (alternative spellings: Nyungar/Nyoongar/Nyoongah/ Nyungah/Nyugah/Yunga) have lived in the area and had possession of tracts of land on their country for at least 45,000 years. Noongar are made up of fourteen different language groups (which may be spelt in different ways): Amangu, Yued/Yuat, Whadjuk/Wajuk, Binjareb/Pinjarup, Wardandi, Balardong/Ballardong, Nyakinyaki, Wilman, Ganeang, Bibulmun/Piblemen, Mineng, Goreng and Wudjari and Njunga. Each of these language groups correlates with different geographic areas with ecological distinctions.

WAtoday (2009), Wellington Dam among two new sites added to the WA Heritage List

Erika Apfelbaum (2010), “Halbwachs and the Social Properties of Memory,” in Memory: Histories, Theories, Debates, edited by Susannah Radstone and Bill Schwarz.

Wulf Kansteiner (2002), “Finding Meaning in Memory: A Methodological Critique of Collective Memory Studies,” History and Theory 41

Wellington Dam sits within Wellington National Park on Noongar boodja (country) in the south-west region of Western Australia.2 Situated at the intersection of the shire boundaries of Collie, Dardanup, and Harvey on the traditional lands of the Wilman Noongar people, the Wellington Dam precinct has multiple cultural and historical resonances for the communities in the surrounding Collie River Valley. In recognition of this, the dam has been heritage-listed since 2009.3

Titled Reflections, the artwork explores how identity and heritage can be understood through the shared or collective memories that coalesce around a place. Collective memory is a concept first developed by sociologist Maurice Halbwachs, who explored how memory is shaped in relation to the shared values, knowledge, and beliefs of a given social group.4 For Halbwachs and others, our memories assume collective relevance in a social setting, represented through “media of memory” such as artefacts, statues, buildings, and memorial sites.5

Finished installation at Wellington National Park, Western Australia, March 2021 Guido van Helten

Jay Winter (2010), “Sites of Memory” in Memory: Histories, Theories, Debates, edited by Susannah Radstone and Bill Schwarz

In this way, collective memory can be seen as a frame within which individuals in Collie River Valley continue to make sense of their experiences and define what is meaningful to them and their social group – whether at the family, local, regional, or even national level. Collective memories can cement a sense of unified identity, cohering around a particular “site of memory”6 such as Wellington Dam or through shared experiences such as Aboriginal culture and the Stolen Generations, the growth of the Collie township, migration and labour, and recreation by the river.

‘Searching for a collective memory’

Poster developed while researching the mural design, Western Australia, September 2020 Guido van Helten

Through consultation with Noongar representatives, councillors, families in the nearby town of Collie, Collie Retired Miners Association, Roelands Village and Woolkabunning Kiaka Aboriginal Corporation and others, the artist sought to explore the concept of collective memory expressed through three elements of cultural heritage: built heritage represented by the Wellington Dam site; the natural heritage of Collie River and the surrounding national park; and material heritage represented by historical photographs associated with those places.

Stakeholders were asked to reflect on these aspects of heritage, to share their memories of the dam precinct, and to submit “artefacts” of these memories in the form of family snaps. As van Helten explains:

Guido van Helten, artist notes

The purpose of the consultation process [was] to resolve questions on the importance of local heritage, and why and in what ways communities are drawn to the memorialization of the past through storytelling, monuments, and murals. It sought to find objects in which these collective memories are inscribed — focusing on historical family photographs and storytelling.7

Photographs at the Collie Mineworkers Institute, Western Australia, September 2020 Guido van Helten

Photo submissions at the Collie Museum, Western Australia, September 2020 Guido van Helten

Wellington Dam Design Layout, Western Australia, September 2020 Guido van Helten

Ibid.

The mural features six photographs from diverse communities across several generations. The artist made copies of the selected images and arranged them in a pool of water to inform the cohesive mural design, bringing disparate images together “as one”. In doing so, the artist says his intention was to show that the collective story of Collie – and, by extension, the Australian story – is no single story, but rather a compilation of stories from different communities and experiences that provides a unifying identity.8

Roelands Village, Western Australia, September 2020 Roelands Village Archive

Family picture at the Wellington Dam, Western Australia, September 2020 Cain Family Archive

Miloslawa Gryczalowski Family Albums, Western Australia, September 2020 Guido van Helten

The photographs depict migrant workers, school children playing in the water, Aboriginal children on a picnic day out from Roelands, a Collie family huddled on the sand, and an Aboriginal couple from a photograph believed to date from the 1890s.

Although stakeholders offered multiple views on what the dam site represents to their respective communities, van Helten identified a commonality in their photographs and a shared sense of livelihood, communion, and pleasure in the waterways:

Collie Mural Trail, YouTube (2021), Reflections – The Wellington Dam mural by Guido van Helten

What I found was, over generations you have imagery that I found to be similar. The poses, and the people using the space not as its intended purpose but as a place of gathering and meeting. Children would be playing. . . in the waterfront and every family seemed to have a snapshot of that. And I feel like not only people in this region but people who have visited this region may find they have similar imagery.9

Family picture at the Wellington Dam, Western Australia, September 2020 Cain Family Archive

Collie citizens pictured at the Wellington Dam, Western Australia, September 2020 Collie Museum Archive

By bringing together photographs from personal and public archives that evoke these shared values, Reflections is intended to harmonise the diverse aspects of the dam’s cultural heritage, and recognise the past, present, and emerging uses of the river system:

Guido van Helten, as told to Charlotte Elton and Jackson Barrett, The West Australian (February 2021), World’s largest dam mural, Reflections, opened in Collie

The title [Reflections] is a play on not only the natural environment, which is really beautiful, but also memories. . . . I was searching for a collective memory that could speak for all the different communities that have experienced this place.10

‘It’s a blessing’

Beckwith Environmental Planning (2009), Nyungar Values of the Collie River

AIATSIS (2021), The Stolen Generations

Paula Hamilton (2003), “Memory Studies and Cultural History” in Cultural History in Australia, edited by Hsu-Ming Teo and Richard White

For the Wilman Noongar people the Collie River and connected waterways have long held significant social and cultural values – as a source of food and water, recreation, and as a place of spiritual importance.11 Nearby Roelands Village, a former mission housing Aboriginal children removed from their families, connects the site to the history of the Stolen Generations. The “Stolen Generations” refers to the thousands of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who were impacted by government policies and practices of separating children from their families and communities.12

For historian Paula Hamilton the concept of collective memory helps to explain the continual presence of the past for members of the Stolen Generations, on whose lives the removal of children has left a lasting and intergenerational impact. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identification with the collective memory has also helped bring to light stories of trauma and loss in a political culture that has contested the extent of the policies’ damage.13

Roelands Village, Western Australia, 1960 Roelands Village Archive

Roelands Village, Western Australia, September 2020 Guido van Helten

Noongar elder Joe Northover,Collie Mural Trail, YouTube (2021), Reflections – The Wellington Dam mural by Guido van Helten

The picture reflects the Mission kids – telling their story, because no one knows their story. And it’s an important one, to how people use and were on the river. . . . I can never instil that [feeling] in people, that feeling of the spirits. When you swim in this water, how it becomes part of you. It’s a blessing.14

Roelands Village, Western Australia, 1960s Roelands Village Archive

Roelands Village, Western Australia, September 2020 Guido van Helten

Roelands Village WA (2021). Roelands Village is located on the Collie River, on Seven Hills Road, Roelands. The property was used as a Mission to house Aboriginal children removed from families from across Western Australia. At times the Mission had more than 100 children living there. Woolkabunning Kiaka means“We’ve Been There, Left and Returned to Seven Hills”.

Today, Roelands Village is managed by the Woolkabunning Kiaka Aboriginal Corporation, and welcomes visitors to learn about the mission’s history and Aboriginal cultural heritage.15 Like Wellington Dam, Roelands is a memory site, one that aims to explicate individual stories within the broader collective context of the Stolen Generations.

Les Wallam, CEO of Roelands Village, in interview conducted by Guido van Helten on October 3, 2020.

There is not one story out at Roelands. What we do as a group is try to respect everybody’s story.16

The entrance to Roelands Village, Western Australia, September 2020 Guido van Helten

‘A very faithful servant to the whole state’

Collie River Valley (2021), Wellington National Park

Wellington Dam and the reservoir which sits behind it have been key features of the local economy, making the site a focal point for collective memories of labour and migration, Depression and boom. In the decades during and following its construction, the dam was a lifeline of employment for many families seeking opportunity in the area. It was originally constructed in 1933, the result of a huge public works effort during the Great Depression era.17 It would go on to become a major employer of post-war migrants from southern and Eastern Europe in the 1950s.

The hard labour of the Depression-era sustenance program workers and European migrants has been recognised in the heritage listing of the Wellington Dam Precinct.18 This heritage also manifests in the collective memories of the families who settled in – and continue to live in – the region.

Miloslawa Gryczalowski Family Albums, Western Australia, September 2020 Guido van Helten

Miloslawa Gryczalowski pictured in her home in Collie, Western Australia, September 2020 Guido van Helten

Miloslawa Gryczalowski, member of a Czech migrant family who settled in the Collie region in the 1950s, in an interview conducted by Guido van Helten on October 10, 2020.

We were standing on the ship in the afternoon, we pulled in that afternoon and all the people were waving to us down on the docks. So we waved back and it wasn’t until later on, we decided that they were chasing the flies and not waving to us!... So we were all waving back, but it was flies.19

Rob Rusconi Family, Western Australia, September 2020 Guido van Helten

Member of the Rusconi family, Italian migrant family who settled in the Collie region in the 1920s and worked on the dam’s construction, interviewed by Guido van Helten on September 30, 2020.

When we go to the weir… we look at it as: ‘Pop did that.’ And that makes us feel a part of it.20

Coal mines west of Collie, Western Australia, September 2020 Guido van Helten

Coal mining landscapes, Western Australia, September 2020 Guido van Helten

Coal mining landscapes, Western Australia, 1950s Collie Museum Archive

Anthony Pancia, ABC News (March 2021), Between a black rock and a hard place; ABC News (March 2019), Collie and coal go hand in hand, but locals fear that could change

Powerful collective memories shaping mining community culture has been observed in many coal towns in Australia and the United Kingdom. See David Selway (2017), Collective memory in the mining communities of South Wales and Ray Christison (2003), The cultural inheritance of coalmining communities

As well as the Wellington Dam, the 1920s and 30s saw the construction of the first coal mines and power stations in the nearby town of Collie. Collie’s coal is used solely to generate Western Australia’s energy grid but, like many coal towns around the world, it is now grappling with a transition away from fossil fuels, and seeking investments in other industries such as agriculture, forestry, and tourism.21

With an estimated 25% of Collie’s residents sustained by the industry, change can be challenging for families whose members have worked in coal for generations – and whose stories and memories have shaped a strong community identification with mining.22 The centrality of this shared history makes it hard to let go of coal, even though many accept the transition to renewable energy is necessary.

Franke Batiste, member of the Retired Miners Association with Italian migrant history, in interview conducted by Guido van Helten on October 7, 2020.

My heritage, it’s all to do with coal – my father in Italy and my grandfather before him… It’s all been involved around coal, so in my point of view, the coal industry here especially in WA has been a very faithful servant to the whole state. It’s been very, very important, although I can see the end of it now.23

The Collie Mineworkers Institute, Western Australia, September 2020 Guido van Helten

Consultation at the Collie Mineworkers Institute, Western Australia, September 2020 Guido van Helten

‘The river is like a lifeline’

The shifting status and function of the Wellington Dam precinct provides a model for change that allows for respect and remembrance of the past while cultivating more sustainable uses for the future. While the dam still services the Collie River Irrigation District, it has long been decommissioned as a drinking water source. These days its location within the Wellington National Park makes it a popular site for nature-based tourism and recreational activities such as camping, picnicking, bushwalking, swimming, fishing, and canoeing.

The Collie River at Collie, Western Australia, January 2021 Guido van Helten

Danielle Cain, Collie Mural Trail, YouTube (2021), Reflections – The Wellington Dam mural by Guido van Helten

The river is everything. It’s what we used to do, where we used to hang out. The water is what brings everyone to Collie. I suppose the river is like a lifeline, isn’t it? Without water the town wouldn’t be here. And since then, since having my own kids here in Collie, we’ve been fishing, marroning, coonacking, and kayaking and spent quite a bit of time on the river.24

Photo Submission, Western Australia, September 2020 Guido van Helten

By exploring the ways in which the dam site has created and facilitated shared memories of work, leisure, and togetherness in the local communities, the artwork Reflections is intended to connect images of the region’s past in an effort to shape a collective, ecologically conscious future of the place for generations to come.

Kelly Lynn,Collie Mural Trail, YouTube (2021), Reflections – The Wellington Dam mural by Guido van Helten

To me I want to protect the environment so our children’s children can enjoy what we enjoy… Preserving what’s here and allowing normal, natural ecosystem to stay in balance is very important to everybody.25

The Collie River at Collie, Western Australia, January 2021 Guido van Helten

‘Where the water goes over the rock’

Final week working on the installation, Wellington Dam - Western Australia Frances Andrijich for Australian Geographic

Final week working on the installation, Wellington Dam - Western Australia Frances Andrijich for Australian Geographic

Final week working on the installation, Wellington Dam - Western Australia Frances Andrijich for Australian Geographic

Collie Water (2018), Wellington Dam

The completed artwork spans an enormous 8000 square metres. Wellington Dam is the largest reservoir in the region and the second largest in the country with the wall measuring 366 metres across and 34 metres high.26 Van Helten camped on site for four months to complete the project. To emphasise the site’s natural surrounds, he worked with a colour palette that was drawn from colours observed in the area:

Collie Mural Trail, YouTube (2021), Behind the scenes of the Wellington Dam mural

When working with concrete I’ll often match to the concrete, so that it looks almost like a tattoo on that surface. In this scenario here, I was really starting to look around, towards the ground, and toward the textures in the rock and in the nature and where the water goes over the rock, because I want those colours around the base to come up into the piece.27

Mural Detail, Wellington Dam - Western Australia Roxanne Taylor

Mural Detail, Wellington Dam - Western Australia Roxanne Taylor

Wellington Dam Mural, Western Australia, March 2021 Guido van Helten

Utopia

Grenoble, France, 2022

Completed for Grenoble Street Art Festival in October 2022.

L'eau - Martigny

Martigny, Switzerland, 2021

The concept explores a site-specific story relating to the Water...

Monuments Project - Minnesota

Mankato, Minnesota, 2020

Minnesota’s largest mural, this artwork is installed at the Ardent...

Monuments Project - Iowa

Fort Dodge, Iowa, 2018

The largest mural in the state of Iowa, this 360-degree mural on...

The Gods of Dharavi

Mumbai, India, 2017

A collaborative concept with the Slum Gods crew - developed on...

FestiWall

Ragusa, Sicily, Italy, 2017

Commissioned for the 2017 FestiWall public art festival, this...

Coonalpyn

Coonalpyn, South Australia, 2017

Commissioned by Coorong District Council at the Viterra active...

Frontline

Avdeevka, Ukraine, 2016

Painted for Art United Us project in the front line town of...

Mexicable Project, Part I

Ecatepec de Morelos, Mexico , 2016

Part of a series commissioned by Konect1 to launch the Mexicable...

Crystal Ship

Oostende, Belgium, 2016

Painted for the first edition of The Crystal Ship arts festival in...

Brim Silo Project

Brim, Victoria, Australia, 2016

The Brim silo project undertaken by Guido van Helten & Juddy Roller...

Last meal on Halvmåneøya

Svalbard, Norway, 2015

Titled Last meal on Halvmåneøya (Half Moon Island) this work was...

Wall to Wall Festival

Benalla, Victoria, 2015

This work explores the use of old photographs in the modern...

Akureyravaka

Akureyri, Iceland, 2014

'Painted for Akureyrarvaka Menningarnótt (culture night) in 2014...